OECD Economic Outlook 2021, Issue 2: A difficult balancing act in getting out of the crisis

17 December 2021

Published on 1 December 2021, the latest OECD Economic Outlook confirms that the global economy is in recovery, while the world enters the third year of COVID-19. Yet, the optimistic forecast seems somewhat more cautious than in previous editions, with more downside than upside risks to the OECD central growth scenario.

The recovery is losing momentum while inequality is on the rise

The economic rebound triggered by the restart of economic activity in most countries has lost momentum, due to supply chain bottlenecks, rising inflation and the emergence of new COVID-19 mutations. The OECD believes most advanced economies to return to 2019 GDP levels by 2023, but this trend is well below pre-pandemic growth projections, signifying a considerable loss in income for most households.

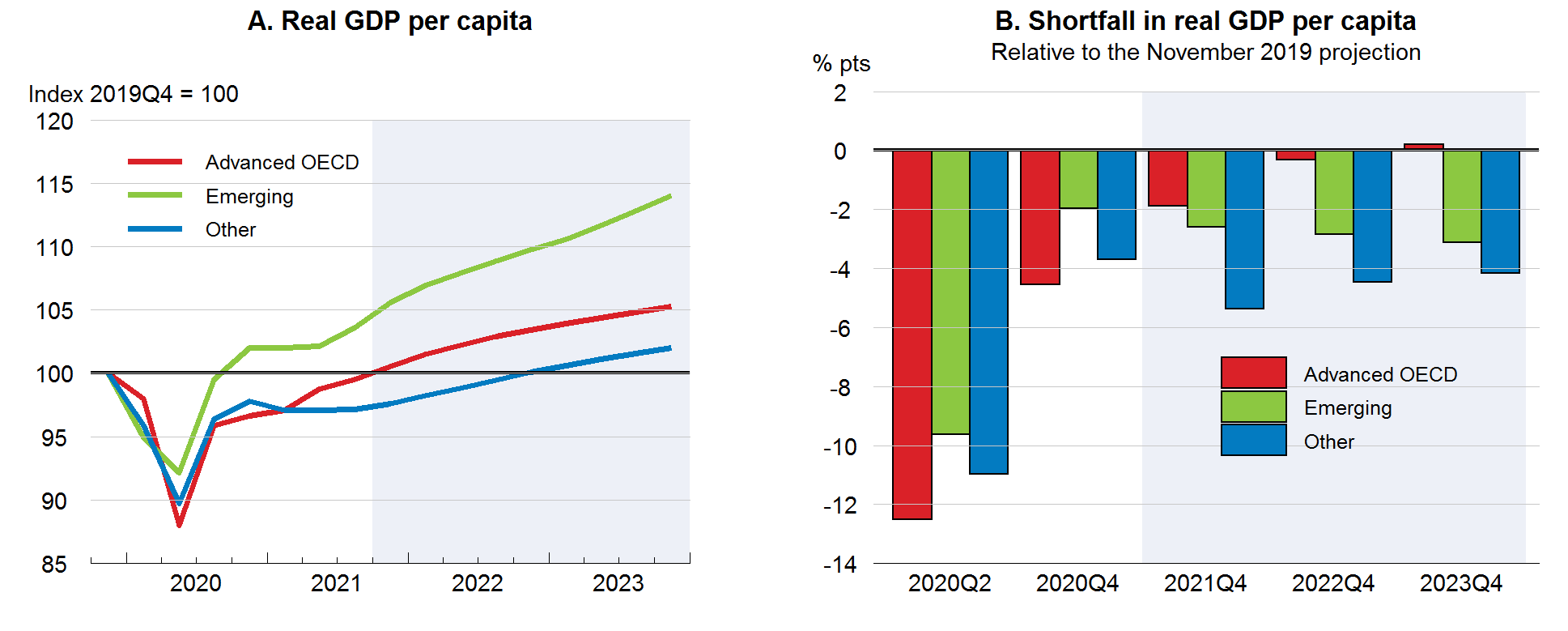

Most important, increasing inequality between and within countries is becoming an entrenched phenomenon in the current recovery. Countries with adequate health systems and access to COVID-19 vaccines are recovering faster than those without, particularly in the Global South (Figure 1). Sectoral differences play a role within single economies, with some sectors reopening or better adapting to the changing conditions imposed by COVID-19, whereas others, mostly contact-intensive sectors, are still facing difficulties in returning to pre-pandemic levels. While the degree of permanent structural change that COVID-19 will bring across sectors is hard to assess yet, negative long-term consequences will be considerable, particularly for workers in low-skilled jobs that the crisis will make redundant.

Figure 1 – A diverging economic recovery

Note: Advanced OECD is OECD minus Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico and Turkey. Emerging comprises the latter five OECD countries plus the BRIICS plus Argentina, Bulgaria and Romania. Other is all countries excluding the above, the Dynamic Asian economies (Chinese Taipei, Hong Kong, China, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam), and a number of oil-exporting countries. The Other grouping mostly consists of lower-income developing economies.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook 110 database; OECD Economic Outlook 106 database; and OECD calculations.

Labour market trends

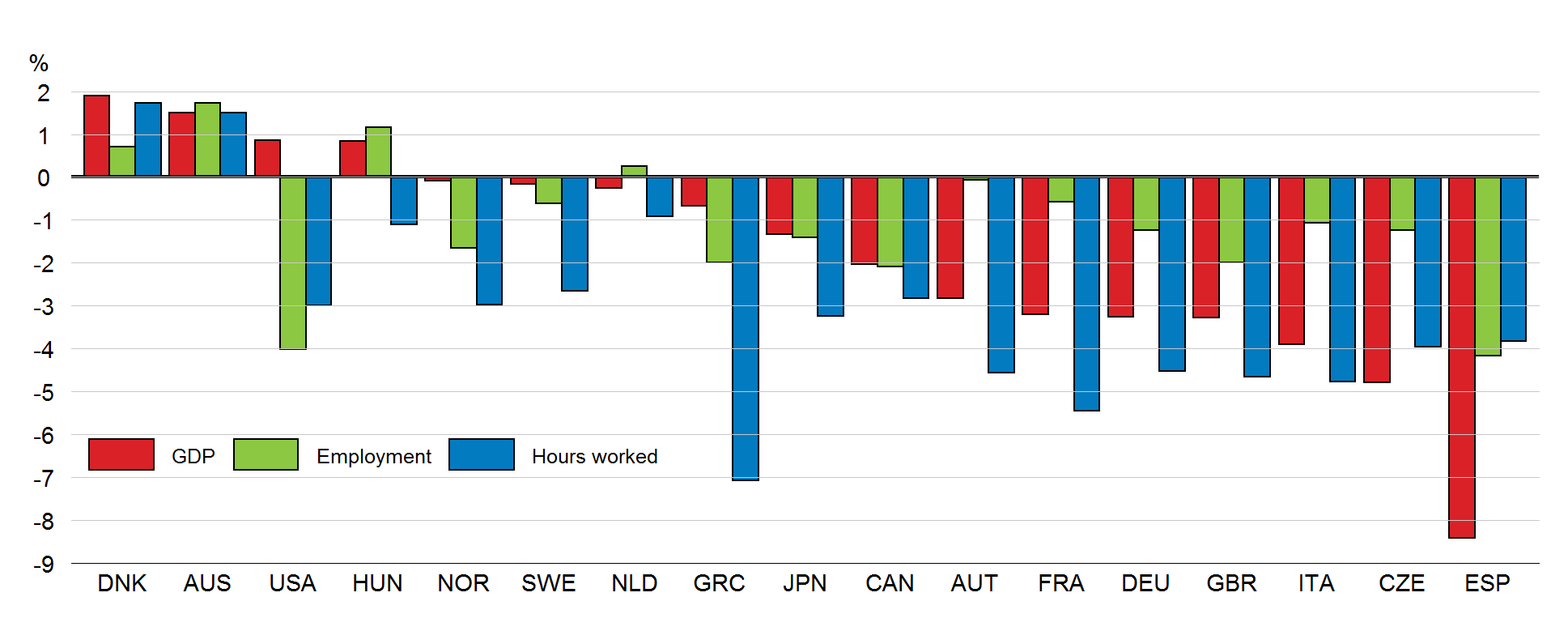

By the third quarter of 2021, 7.5 million more workers were out of employment than in fourth quarter of 2019. Even where employment rates have recovered to pre-crisis level, the total number of hours worked is still below that of 2019 (Figure 2).

Figure 2 – The labour market lags behind GDP recovery in most OECD countries (percentage change between 2019Q4 and 2021Q2)

Source: OECD Economic Outlook 110 database; Bureau of Economic Analysis; Statistics Canada; Australian Bureau of Statistics; Statistics Bureau, Japan; Eurostat; Office for National Statistics; and OECD calculations.

The OECD also notices an important drop in the size of the labour force, particularly in Latin American countries, the United States, Turkey and Israel, with many workers deciding to retire early. Yet, the most important phenomenon is that of long-term unemployed who stopped searching for jobs in the context of on-and-off restrictions to economic activity.

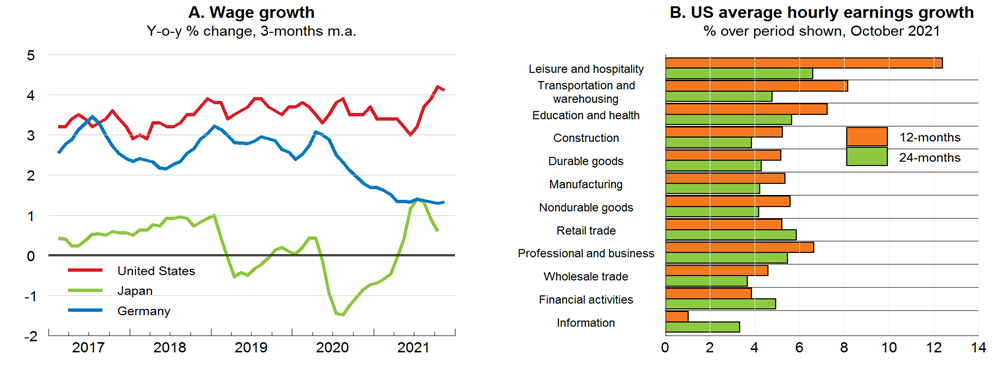

Currently, there is a rising labour shortage in some markets and sectors, particularly in the United States. This is due to halted migration workforce streams, due to barriers to physical cross-border movement amid the COVID-19 pandemic, and the lack of widespread firm-worker preservation mechanisms (a.k.a. job retention schemes) in the US, compared to many European countries for example. Yet, it is not enough to put pressure on real wages, which according to OECD data will remain stagnant in the coming period (Figures 3 and 4). Under the central growth scenario projected by the OECD, employment rates are expected to recover to pre-crisis levels by end of 2022.

Figure 3 – Aggregate wage pressures remain feeble despite rising labour demand

Note: The wage measures in Panel A are: the median change in hourly wages of individuals observed 12 months apart in the United States; contractual cash earnings in establishments with five or more employees in Japan; and negotiated wages excluding one-off payments in Germany.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta; Bureau of Labor Statistics; Destatis; Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan; and OECD calculations.

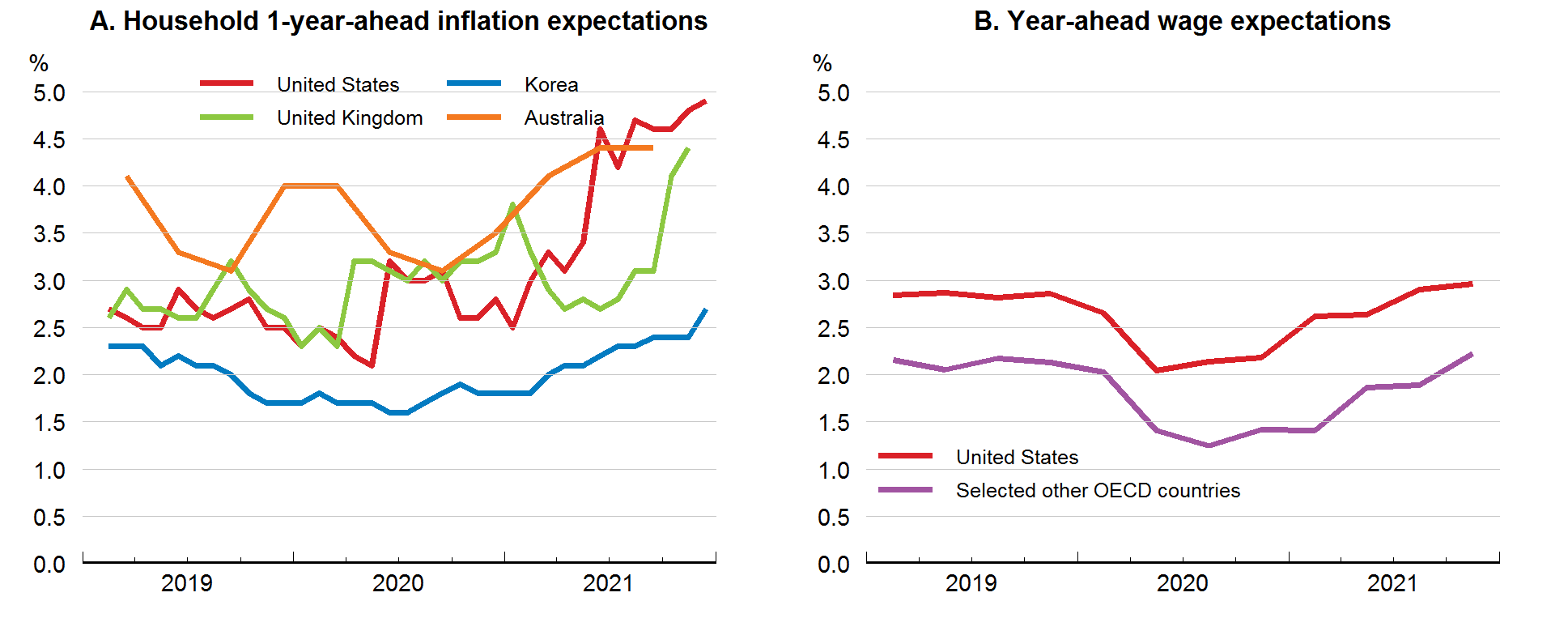

Figure 4 – Limited wage growth projections despite rising inflation expectations

Note: In Panel B, ‘Selected other OECD countries’ corresponds to a weighted average of other OECD countries for which comparable wage expectations data are available: Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Countries are weighted by employment levels. The value for 2021Q4 is based on the October value for the United States, and is available only for New Zealand, Norway and the United Kingdom for the aggregate.

Source: Refinitiv; Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development; Bank of Canada; and OECD calculations.

Throughout this edition of the Economic Outlook, inflation returns as an important downside risk factor, if it proves stronger and longer lasting than the OECD expects. Factors that could lead to this include prolonged supply chain frictions (demand outpacing supply), entrenched higher inflation expectations, broad-based diffusion of price increases across services and products, increased housing prices and tight labour market conditions.

Focusing on the latter, the OECD recalls the 1970s scenario, in which sustained energy and product inflation triggered a constant demand for rising wages and price inflation for years. The Economic Outlook reassures the readers that this should not be the case today, because of «changes in labour market institutions since the 1970s», most notably a «decline in coverage of collective bargaining agreements, the removal of many automatic wage indexation mechanisms and a reduction in employees’ bargaining power due to lower union membership».

What the OECD fails to notice is that while the erosion of labour market institutions might indeed limit inflation spikes, it is not only a “neutralised risk”. It also represents a considerable issue in setting single economies back on track, by rebalancing bargaining power between workers and employers, securing higher real income, boosting aggregate demand and reducing spiking income inequality. Recent OECD evidence shows indeed that one third of overall wage inequality across firms is the result of excessive wage-setting power by the employers in existing conditions of labour market monopsony, rather than a reflection of labour productivity and skills. Addressing these problems, including through strengthening collective bargaining mechanisms to re-balance workers and employers wage-setting power, should represent a key policy priority for most OECD countries, rather than a footnote to inflation consideration issues.

The OECD recipe moving ahead

To support the recovery, the OECD reiterates the policy mix presented in recent editions of the Economic Outlook:

- Deploy and speed up vaccination campaigns (but the Organisation remains unfortunately sceptical about the need for a vaccine waiver in support of developing countries);

- Prolong macroeconomic policy support for as long as uncertainty related to COVID-19 remains high and labour market conditions fragile;

- Do not curtail expansionary monetary policy just yet, despite rising inflation pressure that the OECD deems transitory, while central banks should provide clear medium-term policy indications in order for operators to anchor their expectations;

- Maintain flexible fiscal policy, re-locating rather than cutting down fiscal expenditure, from emergency to structural expansionary policy (investment in education, digitalisation, green economy, etc.). According to OECD Chief Economist Laurence Boone, «we are more concerned by the use made of debt than its level». This seems by now to be a definitive cultural shift of the OECD on the role and sustainability of public finances, compared to the 2010s’ post Global Financial Crisis austerity stance.

- Concrete policies in the recovery, besides tackling digitalisation through innovation and climate change through low-emission targets and carbon-pricing mechanisms, include income support to most vulnerable households, activation and up-skilling measures, and removal of market-entry barriers. While renewed attention to the weakest groups in society is fundamental and welcome, OECD recommendations for labour market policy rely as usual too much on the supply, rather than demand side of the equation.