Collective bargaining put under the OECD’s magnifying glass – Release of the OECD report “Negotiating our way up”

18 November 2019

Executive summary

Collective bargaining and the very existence of trade unions have not always been seen favourably in OECD reports in the past. This is changing. In recent years, a more positive stance can be seen in the revised Jobs Strategy, and the 2018 & 2019 Employment Outlooks. Now, the organisation dedicates a flagship report to collective bargaining, “Negotiating our way up”[i]. It confirms:: “collective bargaining matters for some of the policy objectives that policy makers and citizens care most about: employment, wages, inequality and productivity” . It concludes that there no real alternative to social dialogue, collective agreements and workers’ voice.

The report concludes that healthy social dialogue contribute to productivity gains since “the quality of the working environment is higher on average in countries with well-organised social partners and a large coverage of collective agreements”. It shows that collective bargaining helps to ensure that “all workers and companies, including small and medium-sized enterprises, reap the benefits of technological innovation, organisational changes and globalisation, in a context of increased competition and fragmentation of production”. The report recommends to extend collective bargaining to more workers. It also highlights a wider scope of issues under CB systems (working time, technological standards, training, OHS, discrimination).

The main findings discuss:

- The positive effects of co-ordinated collective bargaining systems “associated with higher employment, lower unemployment, a better integration of vulnerable groups and less wage inequality than fully decentralised systems” (p. 112).

- The report does not link the weakening of collective bargaining coverage and of trade union density to past structural reforms. However, it does flag the negative economic consequences and the risk for OECD countries of finding “themselves without relevant and representative institutions to overcome collective action problems and strike a balance between the interests of workers and firms in the labour market” (p. 17).

- The “insider versus outsider” stigma associated with collective bargaining is debunked: Not only do trade unions try to cover non-standard workers despite competition law and new business models, coordinated CB systems also result in lower youth, women and low-skilled unemployment (p. 113).

- Administrative extension (of collective bargaining agreements to non-affiliated workers) is not a one-to-one substitute for collective organisation but can be an alternative to support wider coverage. However, the OECD recommends to submit it to representativeness criteria as well as to a “public interest” test, which are not necessarily in line with ILO principles and definitions.

- For the first time, the OECD looks into the impact of collective bargaining and workers’ voice along five non-monetary dimensions (occupational safety and health, working time, training and re-skilling policies, management practices, and the prevention of workplace intimidation and discrimination). In a simplified correlation analysis, the distribution of job demands and ressources is compared along three dimensions: (i) representative voice (via trade unions and regulated works councils), “direct” (employer channels to individual workers) and (iii) mixed voice. The report’s approach raises concerns about undefined, and hence unstable, direct voice channels. Most importantly, to ensure that representative and direct forms are not pinned against one another. The results leave space for more research needed on social dialogue, sectoral and multi-employer bargaining in setting a lot of non-monetary provisions – not only at the firm level.

- Collective bargaining can help “formulate solutions to emerging issues (e.g. the use of technological tools, or work-life balance)” (p. 15) and define new rights, adjust wages, working time, work organisation; support displaced workers; anticipate skills needs and ensure access to lifelong learning, and allow the implementation of labour market regulation.

- Trade union initiatives adapt to the changing world of work (opening membership to non-standard or self-employed workers) and negotiate collective agreements with platform companies. The OECD confirms barriers to unionisation (including competition law and blurring employment relationships). The OECD points to the importance of the correct classification of the employment status and suggests to expand union membership to new forms of work and the ‘grey zone’.

[i] OECD (2019), Negotiating Our Way Up: Collective Bargaining in a Changing World of Work, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1fd2da34-en.

OECD (2019), Negotiating Our Way Up: Collective Bargaining in a Changing World of Work, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1fd2da34-en.

A more subtle approach to collective bargaining

The scope of the report allows for a taxonomy of different CB systems – showing that the level of bargaining and the degree of coordination have an impact on economic and labour market outcomes. It attests higher productivity gains from healthy social dialogue, and confirms that “the quality of the working environment is higher on average in countries with well-organised social partners and a large coverage of collective agreements” (p. 15). It shows that CB is instrumental to ensure that “all workers and companies, including small and medium-sized enterprises, reap the benefits of technological innovation, organisational changes and globalisation, in a context of increased competition and fragmentation of production” (p. 21).

However, other findings maintain an critical view on the fact that wage premiums are lower, while wage dispersion is smaller in sector-level bargaining systems – which in itself at minimum points to sector-level bargaining lowering income inequalities. The ‘fit for purpose’ discussion also persists on the ability of unions to cover non-standard forms of work or being open to new forms of organisational change (e.g. telework). Notwithstanding, the policy recommendations are balanced on the need to extend CB to more workers, and new activities of unions around several non-monetary aspects to work (working time, technological standards, training) are highlighted.

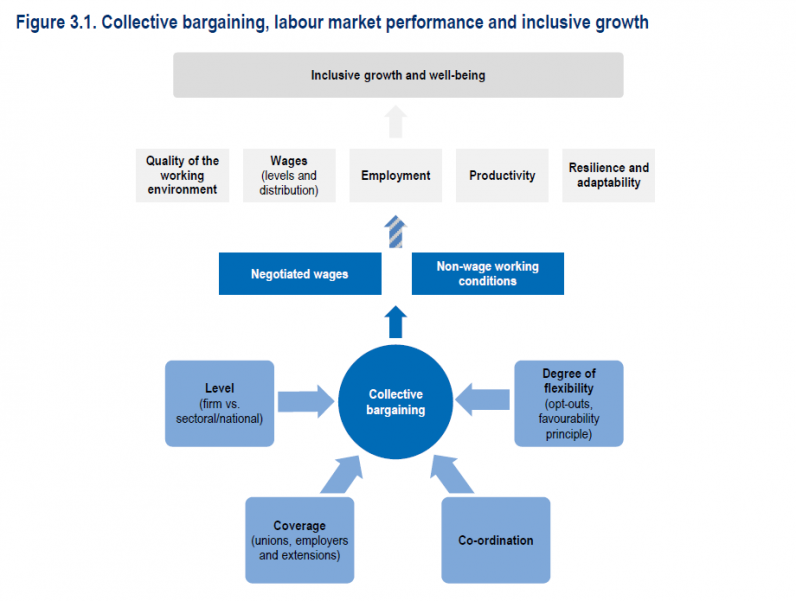

The report states that CB is essential to all three key dimensions of the OECD Job Quality Framework and to inclusive growth (see framework below):

OECD (2019), Negotiating Our Way Up, Figure 3.1. Collective bargaining, labour market performance and inclusive growth (p. 109)

With this hypothesis in mind, the report is based on a wealth of data allowing for a proper taxonomy of CB that provides a more granular view on the complexity of different national systems. The OECD’s policy questionnaire on collective bargaining (also distributed to TUAC members) facilitated the uneasy task. The quality of the report also benefits from the efforts by the OECD secretariat to broaden the source and literature beyond studies almost entirely drawn from common law countries that are not exactly posterchildren of social dialogue and sectoral bargaining. Opening up literature review to non-common law countries indeed allows to better acknowledge how sector-level bargaining provides for a way to better pool risks in case of restructuring, to set wage floors and better working conditions. On that, the present report is a clear departure from the OECD’s historical push for more firm-level bargaining by insisting that the instrument of administrative extension of collective agreements to all firms (and their workers) within a given sector should be phased out (more on that below).

Coordination matters…

The report further stresses the differences between systems: “In two-thirds of OECD countries, collective bargaining takes place predominantly at firm level. Sectoral agreements play a significant role only in continental European countries. However, this does not tell the whole story about the actual degree of centralisation or decentralisation as countries differ greatly in terms of the flexibility for firm-level agreements to modify the terms set out in higher-level agreements” (p. 25). The empirical evidence thus is structured along five different CB systems according to their level of centralisation and coordination. The report also outlines three CB functions (p. 27):

- ensuring a fair sharing of the benefits of training, technology and productive growth (inclusive function),

- maintaining social peace (conflict management function),

- guaranteeing adequate conditions of employment (protective function).

The OECD has come a long way, the new findings confirm the positive effects of co-ordination: “co-ordinated systems are shown to be associated with higher employment, lower unemployment, a better integration of vulnerable groups and less wage inequality than fully decentralised systems” (p. 112). The report’s comparisons display that “co-ordinated systems – including those characterised by organised decentralisation – are linked with higher employment and lower unemployment (also for young people, women and low-skilled workers) than fully decentralised systems. Predominantly centralised systems with no co-ordination are somewhat in between” (p. 105). In conclusion, “co-ordination remains a unique tool to strengthen the resilience of the labour market and increase the inclusiveness of collective bargaining, while safeguarding the competitiveness of the national economy. However, co-ordination not only requires strong social partners at national and local levels, but it also faces increasing challenges to remain effective in a changing economic structure” (p. 134).

… and leads to better labour market health and lower inequalities

Empiricial evidence shows that more centralised CB systems “are also correlated with lower wage inequality for full-time employees” (p. 113). It confirms that firm-level bargaing would not have the same effect on its own: “A cross-country comparison of the averages for the first two groups suggests that firm-level bargaining is only effective in lowering wage dispersion when it comes on top of sectoral bargaining” (p. 116). In terms of employment effects, the report confirms that there is no positive correlation between wage level bargaining and unemployment. Also, “if bargaining also includes the level of unemployment insurance or severance payment, bargaining is described as strongly efficient and employment reaches its optimal level (Cahuc, Carcillo and Zylberberg, 2014[25])”. Bargaining power offsets market concentration dynamics: “when product market competition is imperfect (i.e. when firms have some degree of monopoly or oligopoly power), higher wages may not induce greater unemployment but rather a rebalancing as workers exert bargaining power to increase the labour share. In cases where employers have the power to unilaterally set wages below the competitive wage, maximising profits at a lower level of employment than in the purely competitive framework, stronger bargaining power and higher wage floors can increase employment” (p. 167).

Concern about the weakening of social dialogue

Given that union density and CB numbers are lower compared to past decades, the OECD questions its reach and effectiveness. As of now, “in 2018, about 82 million workers were members of trade unions in OECD countries, and about 160 million were covered by collective agreements concluded either at the national, regional, sectoral, occupational or firm level” (p. 24). The report provides a granular view on composition changes on trade union density (p. 43) by decomposing several variables along workers’ and contract type/ sector/ firm size characteristics. While it discusses sector transformations and changes in employment relationships as factors, the report fails to address the role structural reforms in weakening CB systems – it should have. Thus, it concludes, in perhaps a naïve way, that much of the decline cannot be fully explained.In terms of the policy impact, notwithstanding, the OECD defends the importance of CB: “the weakening of social partners poses the common risk for all countries: that they find themselves without relevant and representative institutions to overcome collective action problems and strike a balance between the interests of workers and firms in the labour market” (p. 17).

The report’s findings also debunk the insider/ outsider stigma attached to CB. Not only do trade unions try to cover non-standard workers despite competition law and business model barriers, coordinated CB systems also result in lower youth, women and low-skilled unemployment (p. 113). However, employers seem to then make more use of temporary employment as ways to decrease labour costs outside of the scope of CB agreements.

Acknowledging the value of administrative extension, but with caveats

As part of the discussion, the report shift the focus to administrative extensions and erga omnes clauses as a factor contributing to lower unionisation numbers: as they “may have weakened the incentives to join a union (as non-union members enjoy the same rights as union members)” (p. 128). The report argues that administrative extensions are not a one-to-one substitute for collective organisation but can be an alternative to support wide coverage of collective agreements when social partners are weak, but have to be well regulated. While it means well, the part on how it should be regulated is the tricky one. Here, the OECD maintains its longstanding recommendation of submitting administrative extension of sector agreements to the condition that the initial collective agreement is signed by employer and/or trade union organisations that representing a ‘reasonable’ share of workers as well as to a “public interest” test, such as the impact on employment (p. 107 & 130). The OECD thereby believes that extension can run counter to the public interest (!), a view that is not shared by the ILO and the approach adopted by many countries, for which public interest concerns such as the need to establish training funds or the need to avoid wage dumping, would precisely facilitate (not restrict) the use of extensions. Experiences with opt-in and out clauses for firms are far from positive. The “troika” (IMF- ECB-European Commission) in the European economies that suffered the most during the financial and euro crisis requested several of these measures. When applied, they resulted in a serious weakening or even an outright collapse of collective bargaining coverage. The case of Portugal where coverage of new collective agreements that update wages fell from 58% of workers to only 9% after imposing a 60% representativeness threshold provides a vivid illustration.

New insights on “direct” and representative worker voices…

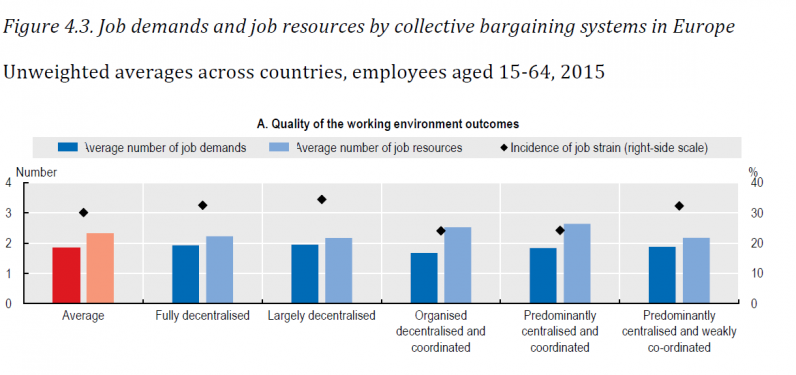

For the first time, the OECD looks in more detail into the impact of collective bargaining and worker representation within firms along five non-monetary dimensions (occupational safety and health, working time, training and re-skilling policies, management practices, and the prevention of workplace intimidation and discrimination). In a simplified correlation analysis based on data from the European Working Conditions Survey, the distribution of job demands and ressources is compared along three dimensions: (i.e. representative voice (via trade unions and regulated works councils), “direct” (employer channels to individual workers) and (iii) mixed voice. The results show that more focus on social dialogue, sectoral and multi-employer bargaining in setting a lot of the provisions on non-monetary aspects is needed – not only at the firm level.

In past consultations, the TUAC has had the opportunity, alongside other stakeholders, to raise concern about undefined, and hence unstable, direct voice channels and most importantly, to ensure that representative and direct forms are not pinned against one another. This is especially important considering that the OECD report does not acknowledge the inherent imbalance of power between workers and employer in a “direct voice” setting and without any representative backing-up the worker. The report eventually flags that: “workers cannot self-select into direct voice arrangements, since the organisation of regular exchanges is not in the hands of workers but largely hinges on employers’ willingness” (p. 175). Another shortcoming of the analysis is that consultation and information rights, and co-determination are barely touched upon.

The report ends up stressing that “direct and representative forms of voice should not be considered as substitutes, notably because of the protections against retaliation and firing, and the information and consultation rights that are attached to the status of workers’ representative, and absent in the case of direct voice” (p. 175).

Either way, the main findings naturally find that ‘mixed forms of voice’ fare best – and representative only forms of voice do not due to ‘reverse causality’ (workers joining unions when working conditions are bad and job strain high): “The positive association between mixed voice and quality of the working environment could reflect the fact that employers and managers who create channels of direct dialogue with their employees are also more likely to engage in improving the quality of the working environment. By contrast, the presence of solely representative arrangements for voice could be characteristic of poor social dialogue contexts, where employers are unwilling to engage in direct exchanges with workers, but are either mandated by law to have representative institutions, or facing dissatisfied workers seeking representation to express their discontents, while benefiting from the legal protections attached to representative voice” (p. 163). The results pointing to reverse causality are basically linked to “poor working conditions might also motivate workers to join unions; unions themselves might primarily focus on firms where working conditions are most in need of improvement” (p. 162).

Not only are these findings easy to misinterpret, they would have benefitted from a more in-depth analysis of representative voice. Also, a major difference between firms hosting representative and those which don’t, is size. Every legislation contains a threshold: below a certain size, it is not practicable to require a firm to organise elections nor to finance permanent structures. As far as board level participation is concerned, there is also the question of whether there is a board in the first place. This “size” element is therefore fundamental when one is analysing industrial relations at firm level.

The analysis shows that job strain is at 30% on OECD average, and lowest Norway (17%), highest in Turkey. In terms of difference across CB systems, more job ressources can be found in co-ordinated systems.

Source: OECD (2019), Negotiating Our Way Up, p. 176

… and their impact on working conditions

The results and examples given on the five dimensions contributing to job quality are an important resource. It shows that further work can be done to build understanding around these different aspects – also with more case studies on CB agreements. This holds true especially since changes across these dimensions are being and will be discussed increasingly with pressing future of work challenges ahead.

On Occupational Health and Safety (OHS), the report finds that having dedicated health and safety representatives in the workplace is associated with improved physical working conditions and a reduced rate of accidents.

On working time, it highlights recent agreements made on working time reductions and flexible work, and points out that “the issue of work-life balance is becoming more important as a topic of negotiations and campaigning” (p. 163). On telework, however, the report finds that such arrrangements are ‘less common in unionised settings’ (p. 186). This assumption does not hold true when considering recent CB rounds that included telework (see for example:

http://www.uni-europa.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/E_HBS-Report-Working-Time_Final.pdf; https://nordicfinancialunions.org/wp-content/uploads/20171117_joint_declaration_telework_banking.pdf; https://www.businesseurope.eu/sites/buseur/files/media/imported/2006-01449-EN.pdf).

On management practices, the report should have distinguished work organisation and management practices more drastically – the former is being handled also at the sectoral and national levels (see introduction of new technologies). Therefore, the report’s focus remains on the firm level: “Work organisation and management practices are primarily the responsibility of management. However, unions and workplace representatives strive to be involved in their definition to ensure that workers also have a say in them.”. When going beyond it, the chapter finds that not only can unions play a role in setting work organisation changes but that “new work organisation and management practices may improve physical working conditions by making work less physically demanding, safer and by giving workers more autonomy and discretion over their tasks. Moreover, they may boost employees’ motivation, work performance and job satisfaction” (p. 191) – wich makes it all the more important to provide more examples but also discuss how positive effects might be diminished when management practices are dictated unless representative voice is involved.

On discrimination, the report does well in outlining the importance of the issue. For the finidings, statistics show that workers are not always seeking the help or confide in workers’ representatives in a situation of discrimination, the report does not put that into context. Furthermore, it delves into a rather unfavourable historical background on the role of trade unions without discussing that the same could be said about all other entities involved and that these findings do not apply to all unions in all country contexts: “unions have not always been at the forefront of the fight against discrimination. Bargaining agendas used to centre on male-biased priorities (Tavora, 2012[132]) and in some cases, unions replicated the type of segregation prevalent in society and in most organisations” (p. 197). Given the importance of this discussion, the adoption of a new ILO convention and more diverse societies, this is an important issue area to explore further.

Overall, the analysis attaches more importance to individual contracts over standard setting and negotiations at any other level, and does not discuss how CB and social dialogue ensure that standards are applied and upheld in more detail than: “a large coverage of collective agreements can diffuse best practices across a large number of companies. Moreover, strong social partners can help ensure a high degree of compliance with provisions spelt out in legislation or collective agreements” (p. 172). Notwithstanding, the report builds a good foundation to go forward in the exploration of the link between job quality and CB/ voice. So, the question is how to overcome limitations on data availability – also to extend beyond European countries – and allow for more country and systems comparabilities.

Non-standard forms of work, new challenges from digitalisation

As in previous recent OECD publication on digitalisation and non-standard forms of work, this report discuss the challenges well and attributes an important role to CB and social dialogue in their resolution. Regarding technological change, the report acknowledges that “collective bargaining, at both sectoral and firm level can also help companies to adapt, through tailor-made agreements and adjustments in the organisation of work to meet their specific needs. Finally, social dialogue can help workers to make their voice heard in the design of national, sectoral or company-specific strategies and ensure a fair sharing of the benefits brought by new technologies and more globalised markets” (p. 250). Collective bargaining can help “formulate solutions to emerging issues (e.g. the use of technological tools, or work-life balance)” (p. 15), as the report illustrates ‘when undertaken in a constructive spirit’ (p. 232) to:

- define new rights, amongst others on the use of new technologies, the right to disconnect from work, and adjust wages, working time, work organisation

- complement public labour market policies by supporting displaced workers;

- anticipate skills needs and ensure access to lifelong learning to adapt to ongoing changes by managing, designing and funding training programmes for workers (see p. 190);

- allow the implementation of labour market regulation in a more flexible and pragmatic way.

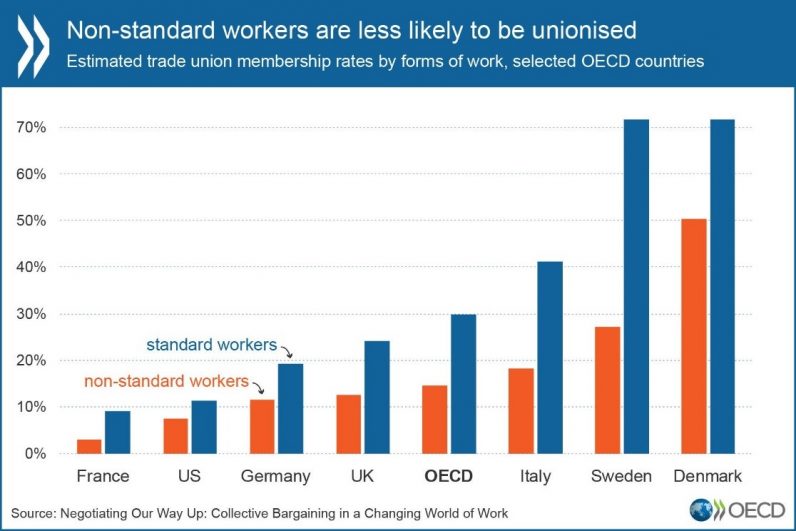

The OECD also confirms that new initiatives are being developed by trade unions to adapt to the changing world of work (opening membership to non-standard or self-employed workers (e.g in the creative sector or for temporary agency workers), negotiating collective agreements with platform companies, engaging in training provision). Data confirms barriers to unionisation as workers in most countries without non-regular jobs remain outside the scope of CB:

To provide access to collective bargaining for different types of workers, the OECD points to the importance of the correct classification of the employment status. The report suggests to expand union membership to new forms of work by:

- tailoring labour law to give workers in the “grey zone” (dependent contractors, false self-employed) the right to collective bargaining;

- exempting specific forms of self-employment from the prohibition to bargain collectively, in particular under competition or cartel law to curtail monopsony power (p. 230 & p. 239).

The tenor of the publication is to seek solutions via CB to manage change and to expand coverage to a diverse group of workers.